Several months back, I was presented with an opportunity to join a new R&D team at my employer. The individuals in the team all had different skill sets and hailed from different backgrounds. What brought them together was a challenge to extract the essence of business offerings from unstructured human-written (often poorly written) reviews using modern NLP techniques, refreshed and updated daily to the tune of hundreds of millions of reviews. This project had been in research mode for some months before my joining the team, but after some internal organizational restructuring, it had piqued the interest of key business and technology leaders and was bestowed a formal team and dedicated (though slim) engineering resources. My own interest in this team came from the opportunity to design and build a scalable NLP computation engine for the task at hand, with a very small set of engineers at my disposal – only one of which had worked on true production systems in the past. Perhaps a daunting task, but I was excited to tackle it – and to learn as many new and unique technologies as I could while doing so.

Upon discussing the current state of the research and implementation with team members, I was surprised to find that the team had chosen Scala as the language choice with Apache Spark as the runtime engine for text processing. Not surprised because I thought this was a bad decision, but rather that my organization was (and still is) currently in some ambiguous stage between “wild-west coyboy driven startup” and “heel-dragging corporate behemoth” which tends to eschew trendy technology choices that don’t have a sizable production legacy (as Java does). Having spent many years with the JVM on Java alone, I became interested in Scala years back – just not enough to do much more than dip my toes in whatever it is one dips ones toes in when investigating a new programming language. Ready to take my JVM-based programming ego down a few notches, I dove into the team head first and was pleasantly surprised by what I found.

Where should we put Scala?

Almost immediately upon quizzing my new teammates for details about their current software, I was bombarded by some highly charged discussions regarding previous technology choices. Comments like “yeah, we’re using Scala because Alice and Bob think that it’s cool”, “nobody supports this here; now that you’re helping us, Taylor, can you re-evaluate Scala’s use?”, and “I hate Scala” were frequent refrains. They were almost as popular as “we really want to run on Spark, and Scala supports many of the computation primitives that I’d rather not write in Python” and “Christine and Dave just need to practice more and they’ll see why Java is for dinosaurs” (names have been changed to protect the innocent). In fact, I myself was at first slightly miffed at being called a “dinosaur” – but I bottled up my own verbal defenses and tried not to be offended. Everyone’s opinion came from a different viewpoint; I wanted to figure out why the reactions had been so polar.

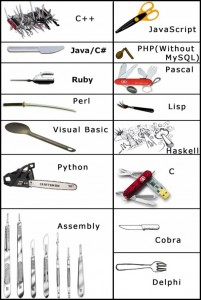

Perhaps the most eager of the Scala-defenders led me to a Paul Graham blog entry from 2001 entitled “Beating the Averages”. (I had actually been led donkey-style to this article in the past, but admittedly didn’t parse past the first few sentences.) In a nutshell, Paul Graham’s argument is that using efficient, non-mainstream technologies (programming languages in particular) that competitors ignore provides a competitive edge. He goes on to talk about “The Blub Paradox” regarding the “power” of computer languages, and asserts that “the only programmers in a position to see all the differences in power between the various languages are those who understand the most powerful one”. He wrote that by choosing a language which he considered at the time to be very powerful, his “resulting software did things our competitors’ software couldn’t do”. (For those interested, a cursory search for “Blub Paradox” provided this page as a counterexample to its merits.) This was the argument presented to me by my co-worker – that by choosing a language more powerful than Java, our team would be able to approach and solve our business problems in a better way that would be harder for others to replicate. While I didn’t take Graham’s comments about his language of choice specifically to heart (Graham speaks very candidly about his love for Lisp), the article and my co-worker’s argument did strike me and I set off to dive into the world of Scala.

One more note from the Scala-defender from above – one of the more compelling statements they made to me was that “Scala raises the level of abstraction from Java by managing language complexity that Java cannot get rid of”. As I travelled along my Scala learning path, I quickly found this to be the case.

The first stop along my foray into Scala came in the form of Scala for the Impatient by Horstmann. Admittedly, I found that I was a bit impatient – I didn’t make it past the first two chapters. Upon reaching chapter three, entitled “Working with Arrays”, I skipped directly to reading my co-workers source code. My own brain learns by looking and manipulating concrete examples, and for me the best way to do this has always been to start with the most familiar pieces of a new domain, such as an existing business process encoded into a computer program.

Having a background in Ruby, Python (with some ancient Scheme / Lisp knowledge) as well as Java, much of what I read seemed to make sense, with a few exceptions. Going to the web and humans for help, I quickly realized what many before me have said – there are many, perhaps too many, mechanisms for achieving very simple logical operations such as method calls, transforms, variable name references, etc. So many that it can be a bit confusing for the relative newcomer, as there are a variety of “canonical” style guides which seem to be produced by different camps in the Scala community. As it was described to me by one co-worker (who is regularly in conversations with Scala and Spark advocates in the San Francisco Bay Area), there are two main groups supporting Scala today: a group which is very interested in using the language as a research tool for language design itself, and a group which is very interested in language feature stability, ease of use and comprehensibility, and wide adoption for community support. Being an engineer who has spent many years in the halls of production hot-fixes, support, junior engineer mentorship, and consensus-building through standards and convention, I quickly realized that I aligned much more closely with the latter camp.

Fast-forward two months. I think I’ve gotten a good grip on how to approach programming from a Scala-standpoint, mostly through writing patches and new features for the previously mentioned big-data processing program running on Spark. In addition to understanding how one uses Scala pragmatically for actually getting real work done, diving into the runtime details has also opened my eyes to how one writes effective programs for Spark (more on that to come later, perhaps). I have a pretty good handle on the build process, how many concepts in Maven builds work with SBT, and what to do when things go wrong. With my newfound knowledge, I coded up a very basic app to prove my skills to myself – see it on Github if you’re interested. I’ll likely go into a little more detail about that project in the future as a very small case study.

Some resources that I found along the way that others might find helpful:

- Books – I don’t really keep language books on hand, as there are typically enough internet resources available with cursory Google searches.

- Scala for the Impatient. Perhaps not the first place I would go personally, but it might be a good suggestion for others.

- Learning Concurrent Programming in Scala. Having an extremely high opinion of a similar sounding book for Java, Java Concurrency in Practice (perhaps the best Java guide to writing correct concurrent programs), I found this book to be lacking. Perhaps that’s because JCIP is so complete, that there isn’t much else to say when thinking about how concurrent programs operate on the JVM. My gut feeling tells me that it’s more likely that there are many Scala concurrency gotchas that just aren’t well-known enough to make this volume really stand on its own.

- Style guides – These are the things that really help me. As far as programming goes, I’m much more interested in convention over flexibility at this point in my life – so having a style that the community generally follows just makes things easier for everyone – myself, my code reviews, and my maintainers.

- Databricks Style Guide. After consulting with a few Scala folks, this seemed to be a very sensible best-practice document for writing Scala code.

- Twitter Style Guide. Probably just as high quality (and obviously written by smart Scala coders), but seems to give the coder a little more rope to hang themselves with when using the language.

- The “Official” Scala Style guide. This was much less useful for me, given that I’m looking for suggestions of “when you need to do x, here is how you should code it”. In my opinion, it suggests too many esoteric Scala constructs that compete with each other, making things more confusing for a Scala newcomer than they need to be.

- Code helpers – Tools for non-omniscient beings, like myself, who do not have said best-practices / conventions memorized and cannot yet write perfect Scala code into a freeform text editor due to our lack of language mastery.

- Scala IDE for Eclipse. The code completion and syntax checking tools seem decent. Certainly worth the three minute install.

- ScalaStyle. Style checker, with a configurable rule set that I tweaked a bit to follow the DataBricks style guide a little more closely.

- Scalariform. Used for Scala code formatting. I’d rather have the auto-formatting in my IDE, but I’ll take what I can get. Actually, I’ve only used this once – so I can’t say I can recommend it (due to lack of experience).

With luck, I’ll continue to learn and grow more proficient with Scala. I think I’m at the point that I’d consider writing my own programs in Scala when starting from the ground up – we’ll see how that goes in the next few months.