A huge portion of the challenge in building a self-driving car is environment perception. Autonomous vehicles may use many different types of inputs to help them perceive their environment and make decisions about how to navigate. The field of computer vision includes techniques to allow a self-driving car to perceive its environment simply by looking at inputs from cameras. Cameras have a much higher spatial resolution than radar and lidar, and while raw camera images themselves are two-dimensional, their higher resolution often allows for inference of the depth of objects in a scene. Plus, cameras are much less expensive than radar and lidar sensors, giving them a huge advantage in current self-driving car perception systems. In the future, it is even possible that self-driving cars will be outfitted simply with a suite of cameras and intelligent software to interpret the images, much like a human does with its two eyes and a brain.

Detecting other vehicles and determining what path they are on are important abilities for an autonomous vehicle. They help the vehicle’s path planner to compute a safe, efficient path to follow. Vehicle detection can be performed by using object classification in an image; however, vehicles can appear anywhere in a camera’s field of view, and may look different depending on the angle and distance.

I created a software pipeline to detect and mark vehicles in a video from a front-facing vehicle camera. The following techniques are used:

- Extract various image features (Histogram of Oriented Gradients (HOG), color transforms, binned color images) from a labeled training set of images and train a classifier.

- Implement a sliding-window technique to search for vehicles in images using that classifier.

- Run the pipeline on a video stream and create a heat map of recurring detections frame by frame to reject outliers and follow detected vehicles.

- Estimate a bounding box for vehicles detected.

Exploring my implementation

All of the code and resources used in this project are available in my Github repository. Enjoy!

Technologies Used

- Python

- NumPy

- OpenCV

- SciPy

- SKLearn

Feature Extraction

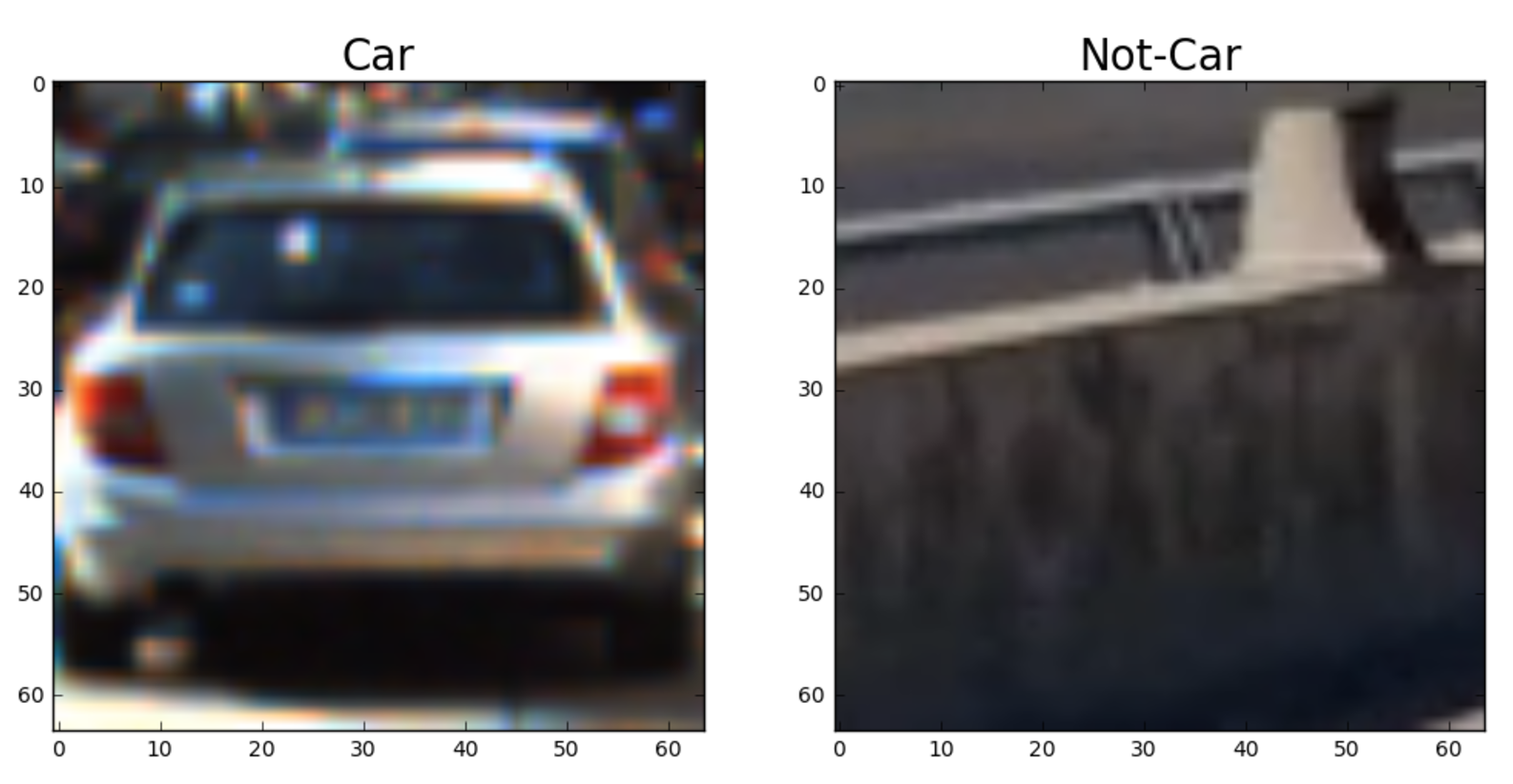

The KITTI vehicle images dataset and the extra non-vehicle images dataset is used for training data, which includes positive and negative examples of vehicles.

Here is an example of a vehicle and “not vehicle”:

Histogram of Oriented Gradients (HOG)

Because vehicles in images can appear in various shapes, sizes, and orientations, appropriate features that are robust to changes in their values is necessary. Like previous computer vision pipelines I have created, using gradients of color values in an image is often more robust than using color values themselves.

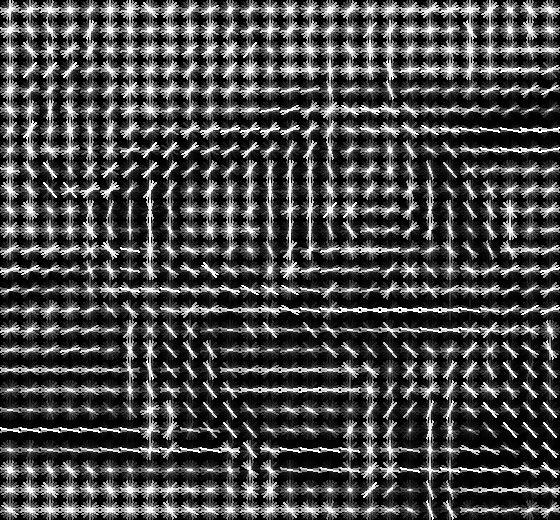

By breaking up an image into blocks of pixels, binning the gradient orientations for each pixel in the block by orientation, and selecting the orientation by the greatest bin sum (by gradient magnitudes), a single gradient can be assigned for each block. The sequence of binned gradients across the image is a histogram of oriented gradients (HOG). HOG features ignore small variations in shape while keeping the overall shape distinct.

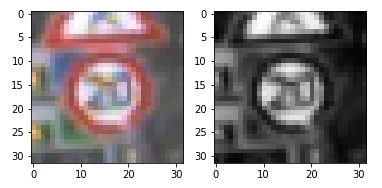

| Original Image | HOG representation |

|---|---|

|

|

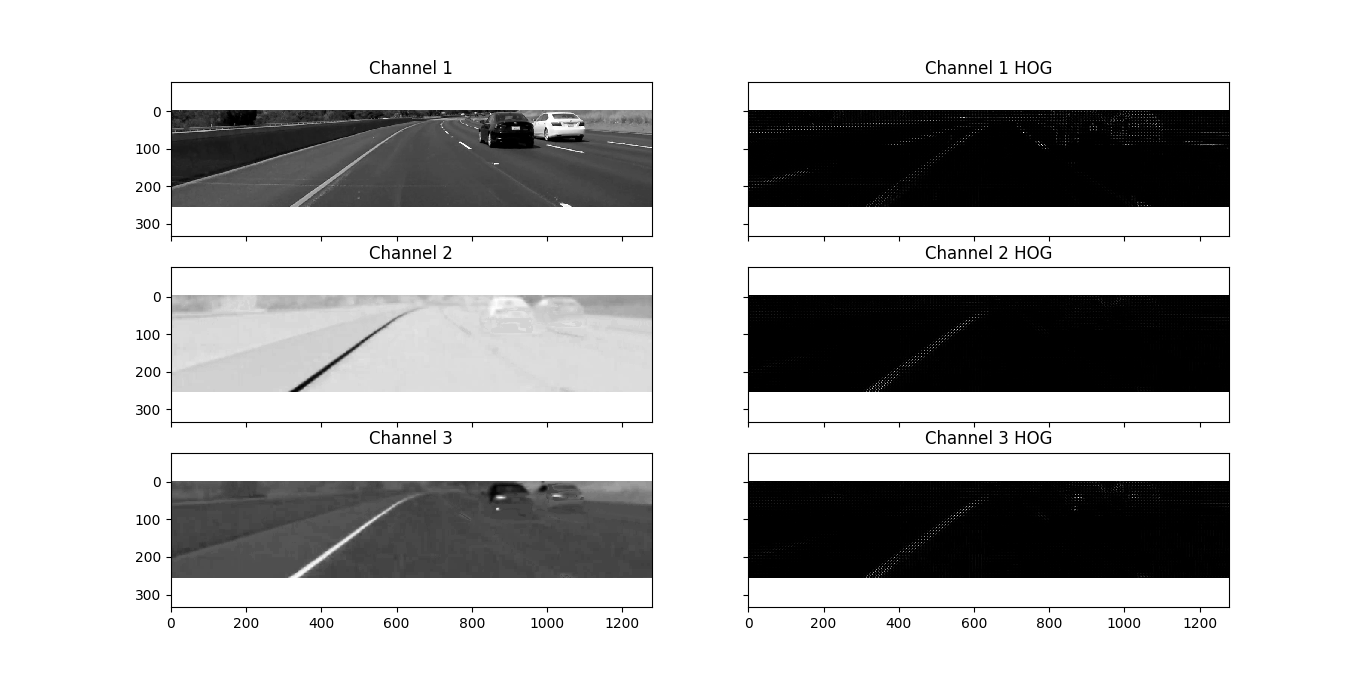

HOG features are extracted from each image in a video stream. First, the color space of the image is converted into the YCrCb color space (Luma, Blue-difference chroma and Red-difference chroma). Next, the color channels are separated and a histogram of gradient features is computed for each channel.

Here is an example of color channels and their extracted HOG features using the YCrCb color space and HOG parameters of orientations=9, pixels_per_cell=(8, 8) and cells_per_block=(2, 2):

HOG parameters

The general development strategy for the pipeline was to increase the accuracy of the vehicles detected in video by tuning one feature extraction parameter at a time: the feature type (HOG, spatial bins, color histogram bins), color space, and various hyperparameters for the feature type selected. While not a complete grid search of all available parameters for tuning in the feature space, the final results show reasonably good performance.

To start, HOG, color histogram, and spatial binned features were investigated separately. HOG features alone lead to the most robust classifier in terms of vehicle detection and tracking accuracy without much tuning; addition of either color histogram or spatial features greatly increases the number of false positive vehicle detections.

Different color spaces for HOG feature extraction were investigated for their performance. RGB features were quickly discarded, whose performance both in training and on sample videos is subpar to the other spaces. The YCrCb color space shows as particularly performant on both the training images and in video compared to the other color spaces investigated (YUV, LUV, HLS, HSV).

Next, various hyperparameters of the HOG transformation were optimized: number of HOG channels, number of HOG orientations, and pixels per cell (cells per block remained at 2 for all tests). In studying the classification results from both test images and video, the following parameters yield the best classification accuracy:

- HOG channels: all

- Number of HOG orientations: 9

- Pixels per cell: 8

Classifier training

Next, a SVM classifier was trained for detecting vehicles in images by extracting features from a training set, scaling the feature vectors, and finally training the model.

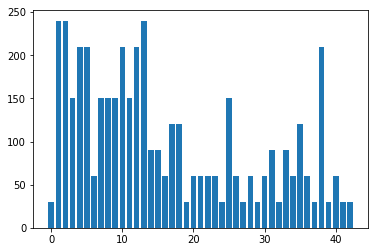

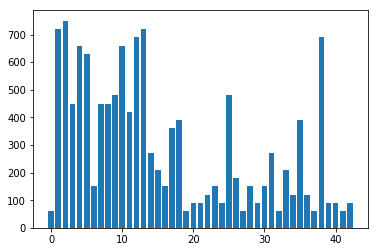

Each vehicle and non-vehicle image had HOG features extracted. To increase the generality of the classifier, each training image was flipped on the horizontal axis in the dataset, which increased the total size of the training data to 11932 vehicle images and 10136 non-vehicle images. The relative equality of the counts of vehicle and non-vehicle images reduces the bias of any classifier towards making vehicle or non-vehicle predictions. Each one dimensional feature vector was scaled using the Scikit Learn RobustScaler, which “scales features using statistics that are robust to outliers” by using the median and interquartile range, rather than the sample mean as the StandardScaler does.

After scaling, the feature vectors were split into a training and test set, with 20% of the data used for testing.

Finally, a binary SVM classifier was trained using a linear kernel (using the SciKit Learn LinearSVC model). Results based on the training data show a 99.82% accuracy on the test data.

Upon completion of the training pipeline, I continued to experiment with other classifiers to attempt to gain better classifier performance on the test set and in videos. To do so, I tested random forests using the SciKit Learn RandomForestClassifier model, using a grid search over various parameters for optimization (using SciKit Learn GridSearchCV), and final voting of classifier based on the SciKit Learn VotingClassifier). The results show that the random forest classifier performs on-par with the support vector machine but requires more hyperparameter tuning, and so the code remains with only the LinearSVC.

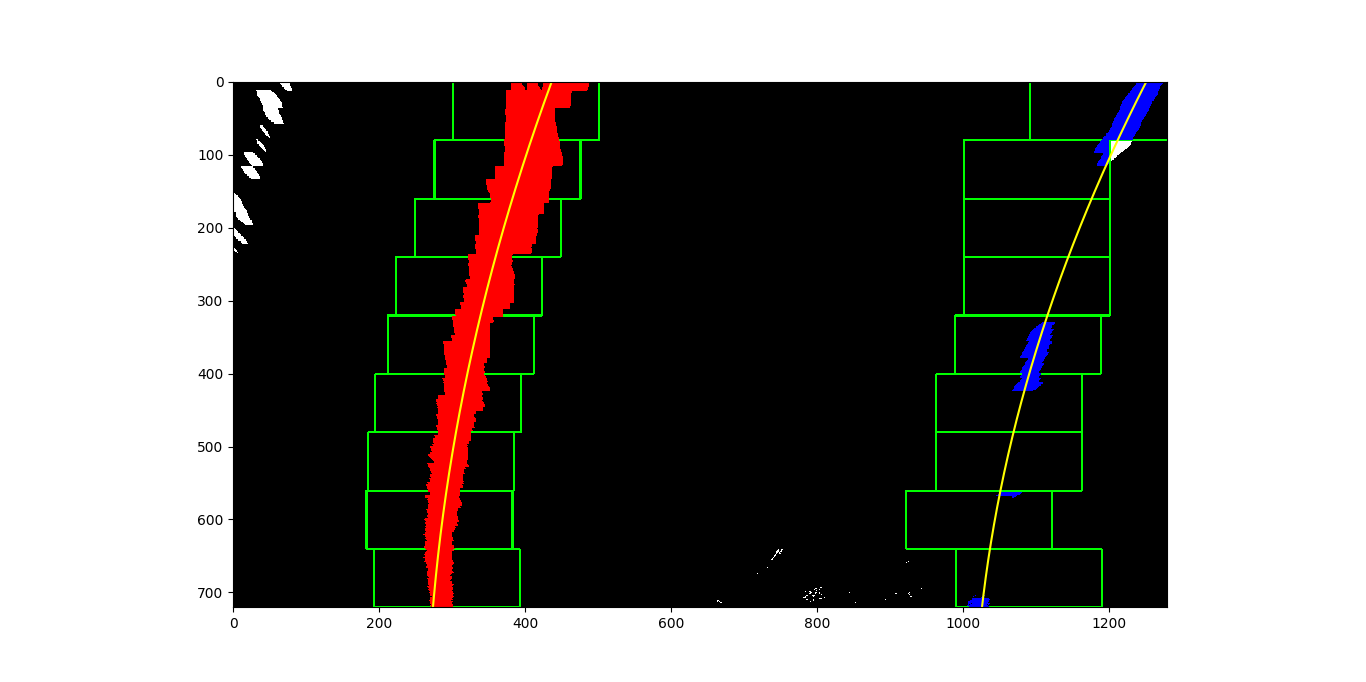

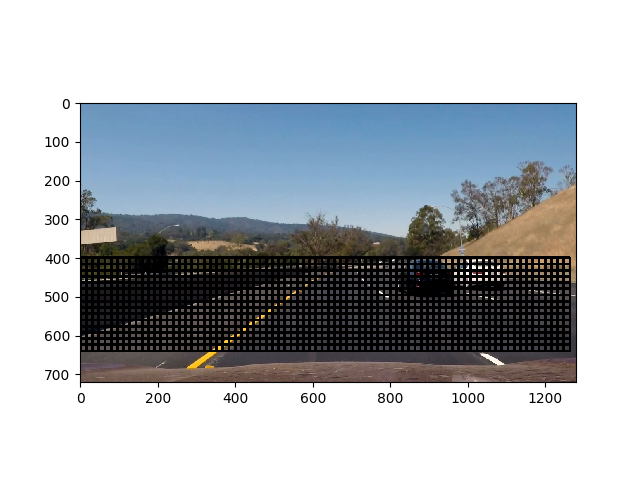

Sliding Window Search

After implementing a basic classifier with reasonable performance on training data, the next step was to detect vehicles in test images and video. A “sliding window” approach is used in which a “sub-image” window (a square subset of pixels) is moved across the full image. Features are extracted from the sub-image, and the classifier determines if there is a vehicle present or not. The window slides both horizontally and vertically across the image. The window size was chosen to be 64×64 pixels, with an overlap of 75% as the detection window slides. Once all windows have been searched, the list of windows in which vehicles were detected is returned (which may include some overlap). As an early optimization to eliminate extra false positive vehicle detections, the vertical span of searching is limited from the just above the top of the horizon to just above the vehicle engine hood in the image (based on visual inspection).

As a computational optimization, the sliding window search computes HOG features for the entire image first, then the sliding windows pull in the HOG features captured by that window, and other features are computed for that window. Together with Python’s multiprocessing library, the speed improvements enabled experimentation across the various parameters in a reasonable time (~15 minutes to process a 50 second video).

In an attempt to improve vehicle detection accuracy in the project video, other window sizes were used (with multiples of 32 pixels): 64, 96, 128, 160, and 192. Overall vehicle detection accuracy decreased when using any of the other sizes. Additionally, I tried using multiple sizes at once; this caused problems further down in the vehicle detection pipeline (specifically, the bounding box smoother).

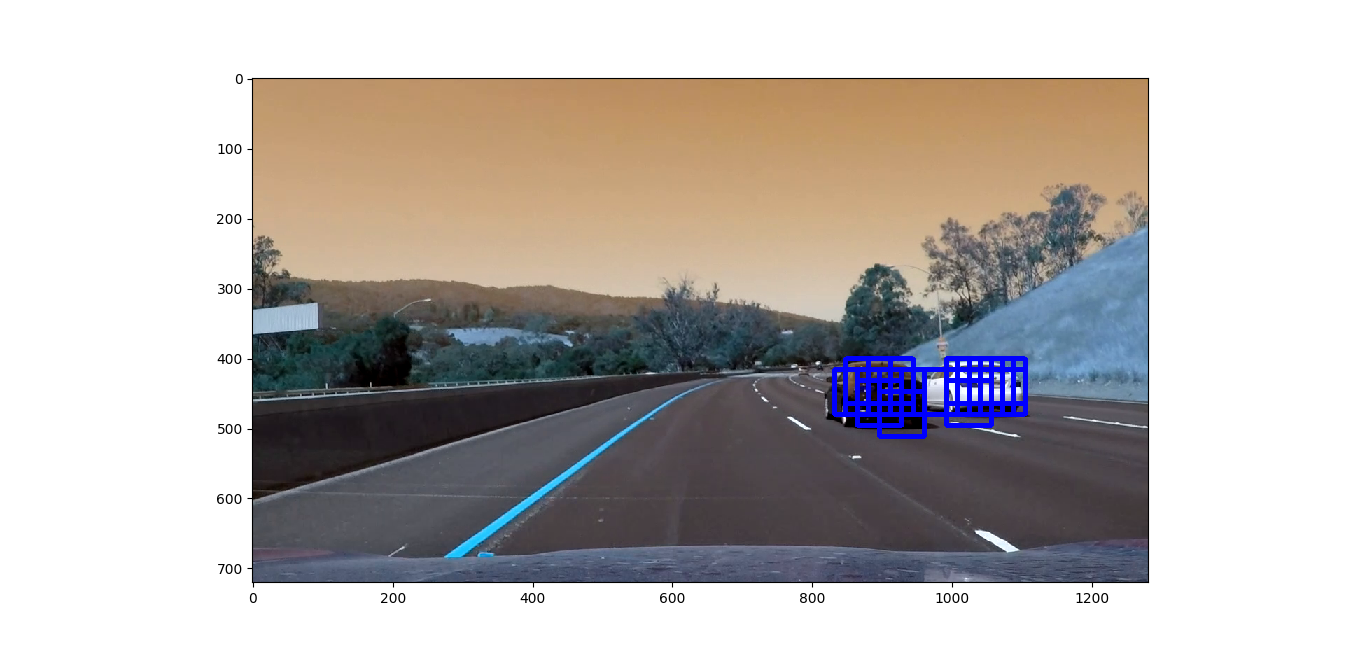

Here are some sample images showing the boxes around images which were classified as vehicles:

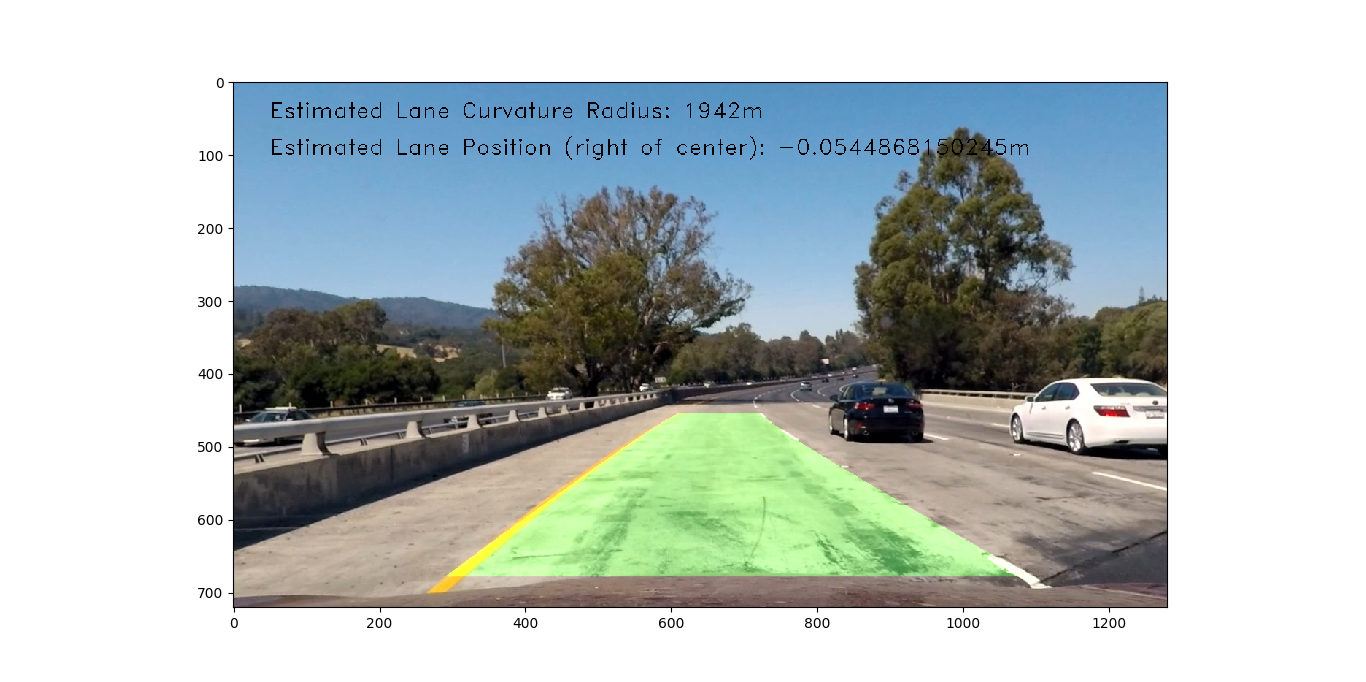

Video

The pipeline generates a video stream which shows bounding boxes around the vehicles. While the bounding boxes are somewhat wobbly, and there are some false positives, the vehicles in the driving direction are identifed with relatively high accuracy. As with many machine learning classification problems, as false negatives go down, false positives go up. The heatmap threshold could be adjusted up or down to suit the end use case.

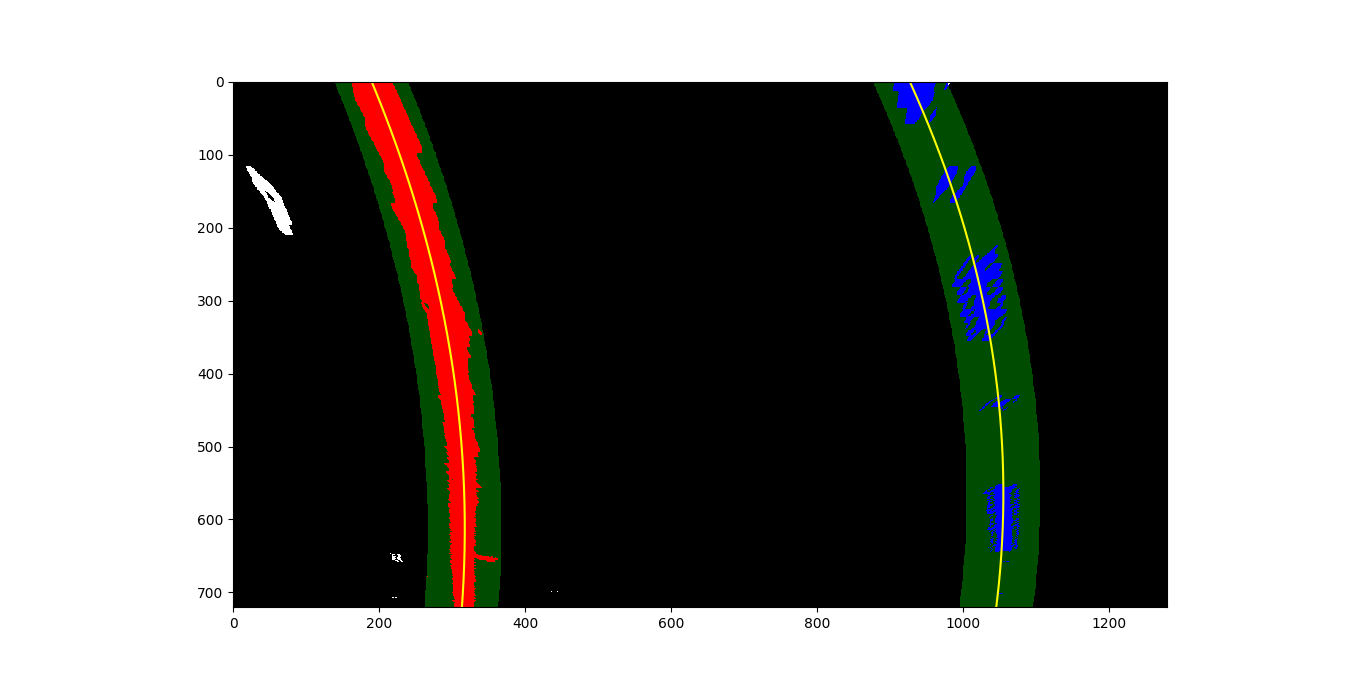

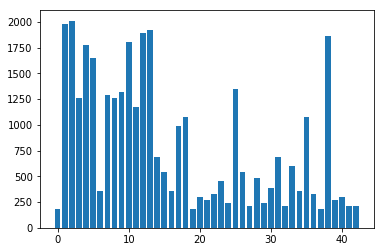

The pipeline records the positions of positive detections in each frame of the video. Positive detection regions are tracked for the current and previous four frames at each frame processing. The five total positive detections are stacked together (each pixel inside a region is one count), and then the final stacked heatmap is thresholded to identify vehicle positions (eleven counts or more per pixel being used as the threshold). I then used SciPy’s label to identify individual blobs in the heatmap. Each blob is assumed to correspond to a vehicle, and each blob is used to construct a vehicle bounding box which is drawn over the image frame.

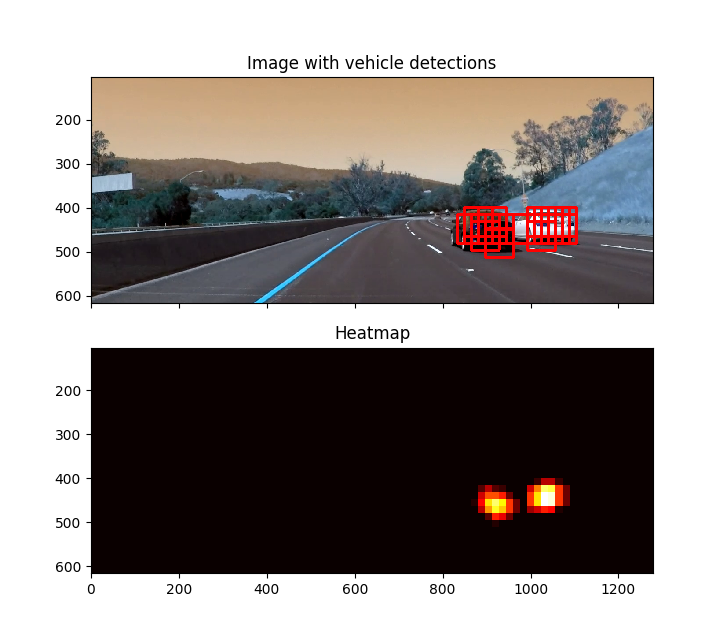

Here is an example result showing the heatmap from a series of frames of video, the result of scipy.ndimage.measurements.label() and the bounding boxes then overlaid on the last frame of video:

Here is a frame and its corresponding heatmap:

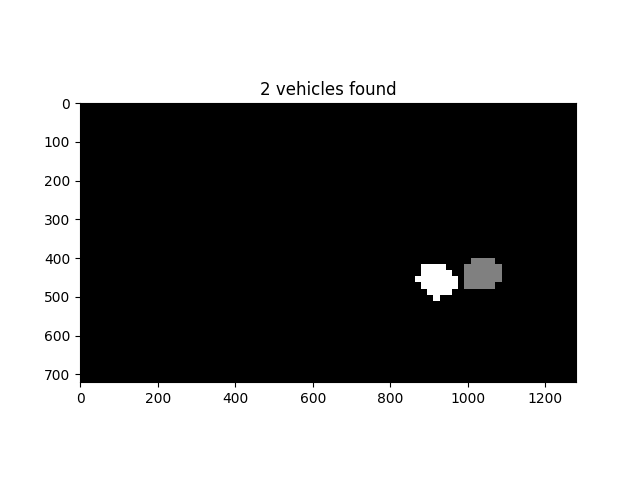

Here is the output of scipy.ndimage.measurements.label() on the integrated heatmap:

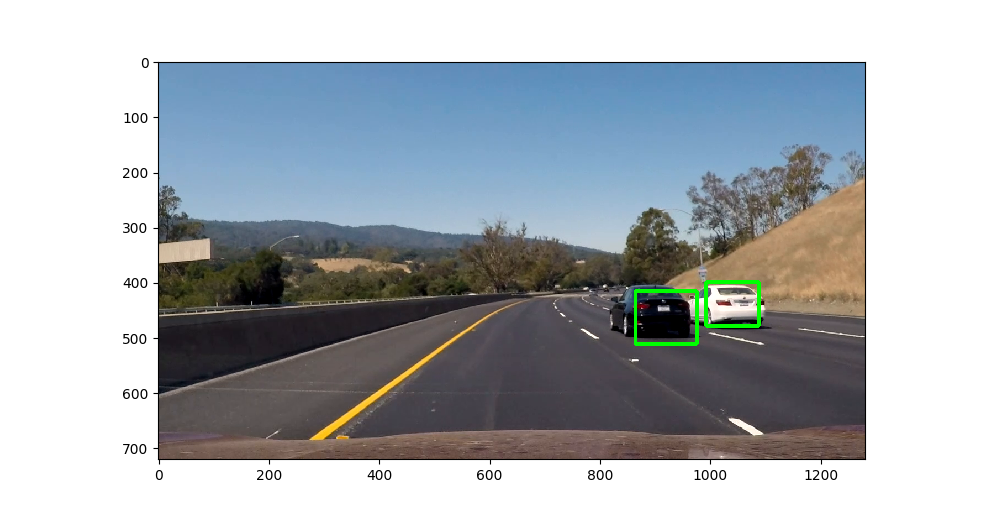

Here the resulting bounding boxes are drawn the image:

Challenges

The most challenging part of this project was the search over the large number of parameters in the training and classification pipeline. Many different settings could be adjusted, including:

- size and composition of the training image set

- choice of combination of features extracted (HOG, spatial, and color histogram)

- parameters for each type of feature extraction

- choice of machine learning model (SVC, random forest, etc)

- hyperparameters of machine learning model

- sliding window size and stride

- heatmap stack size and thresholding variable

Rather than completing an exhaustive grid search on all possibilities (which would not only have been computationally infeasible in a short period of time but also likely to overfit the training data), completing this pipeline involved iterative optimization, using a “gradient descent”-like approach to finding the next least-optimized area.

Problems in the current implementation that could be improved upon include:

- reduction in number of false positive detections, in the form of:

- small detections sprinkled around the video – could add more post-processing to filter out small boxes after final heat map label creation

- a few large detections in shadow areas or with highway signs

- not detecting the entirety of the vehicle

- often the side of the vehicles are missed – include more training data with side images of vehicles

- side detections can be increased by lowering the heatmap masking threshold, at the expense of more false positive vehicle detections

The pipeline would likely fail to detect in various situations, including (but not limited to):

- vehicles other than cars – fix with more training data with other vehicles

- nighttime detection – fix with different training data and possibly different feature extraction types / parameters

- detection of vehicles driving perpandicular to vehicle – adjust heatmap queuing value and thresholding, possibly training data, too