Like Rube Goldberg machines? Then don’t miss the Great Ball Contraption built at 2024’s Japan Brickfest.

Guns in Public Places: Civilian Gun Carrying

This is the eleventh post in a series about Reducing Gun Violence in the United States. The previous post described Waiting Periods and Red Flag Laws.

Up to this point, we’ve explored quite a bit about who can purchase guns, how to purchase them, and what restrictions exist. In this post, I’ll explore different types of civilian gun carrying in public, how that carrying has changed over time, what laws enable it, and what effects civilian gun carrying have on firearm violence.

- For those who want to see the highlights without going through the data, skip right to the conclusions at the bottom of this post.

- The data in this post comes from several different sources, which I’ve linked in the references section at the bottom of this post for those who want to see the data for themselves or dive deeper.

Civilian Gun Carrying

Two primary forms of public gun carrying exist:

- Open carry, in which one can generally see the gun someone is carrying; for example:

- A handgun openly strapped to a belt

- A rifle slung on someone’s back

- Concealed carry, in which the gun is concealed from view; for example:

- In a purse

- In a holster underneath clothing

Open Carry

No broad federal laws exist that regulate open carry of firearms. Most states allow open carry of either handguns, long guns, or both. Some states require a permit for open carry, but most do not. Some states also limit where firearms can be openly carried; for example, restricting open carry of guns in religious buildings or college campuses.

Concealed Carry

Similar to open carry, no broad federal laws exist that regulate concealed carry of firearms. Unlike open carry, every state allows concealed carry in some form. Most states require some type of permit or license for concealed carry. These permits often exempt the permit holder from a federal background check when purchasing a firearm, and also often offer reciprocity between states (a permit in one state may be valid in another without any other action from the permit holder). Some states recognize all concealed carry permits from other states, while others only recognize a select group of other states’ permits (or none at all).

Concealed carry laws fall into three groups:

- May issue

- Shall issue (aka “Right to Carry”)

- Permitless (aka “Right to Carry”)

May issue laws are the most strict. They include baseline requirements for carrying a concealed gun in public, such as having no felony convictions or age restrictions. In addition, even if those requirements are met, the state is not obligated to issue a permit – they might deny issuing a permit based on some likelihood that the permit holder might hurt themselves or others. This is generally called “permit discretion”.

Shall issue laws are less strict. They include similar kinds of baseline requirements as may issue laws, but unlike may issue laws, if a permit applicant meets the requirements, a permit will be issued. The state does not have discretion.

Permitless laws are the least strict. As long as you are legally allowed to own a firearm, then permitless laws allow you to carry it concealed in public with no extra permit or license.

Shall issue and permitless laws are often referred to together as “Right to Carry” laws, which we’ll explore in more depth later in this post.

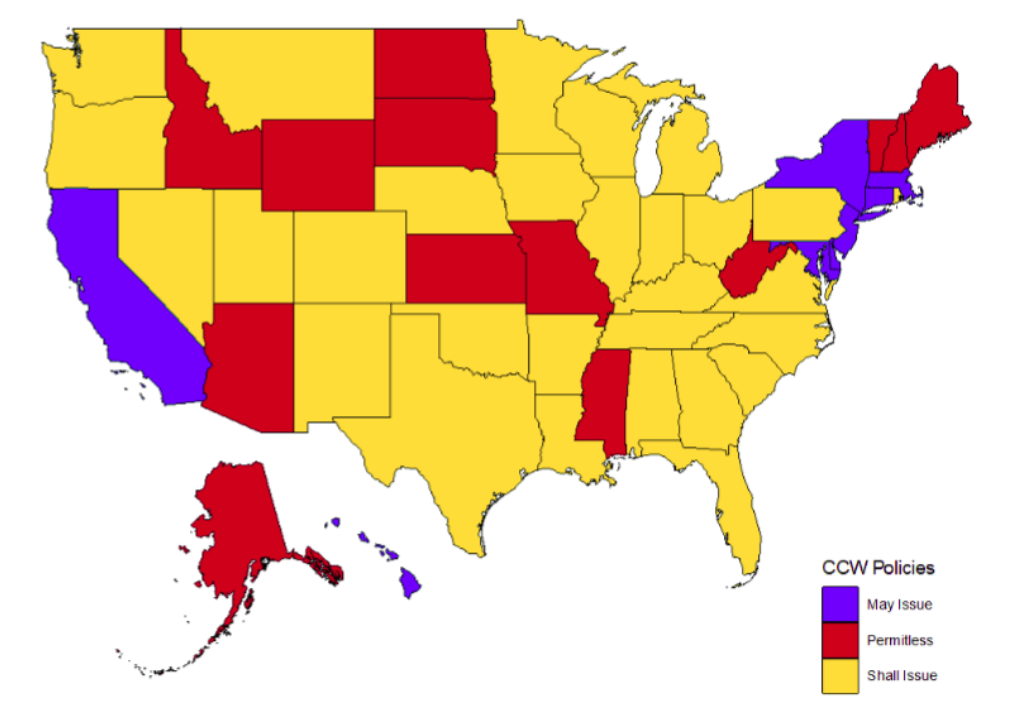

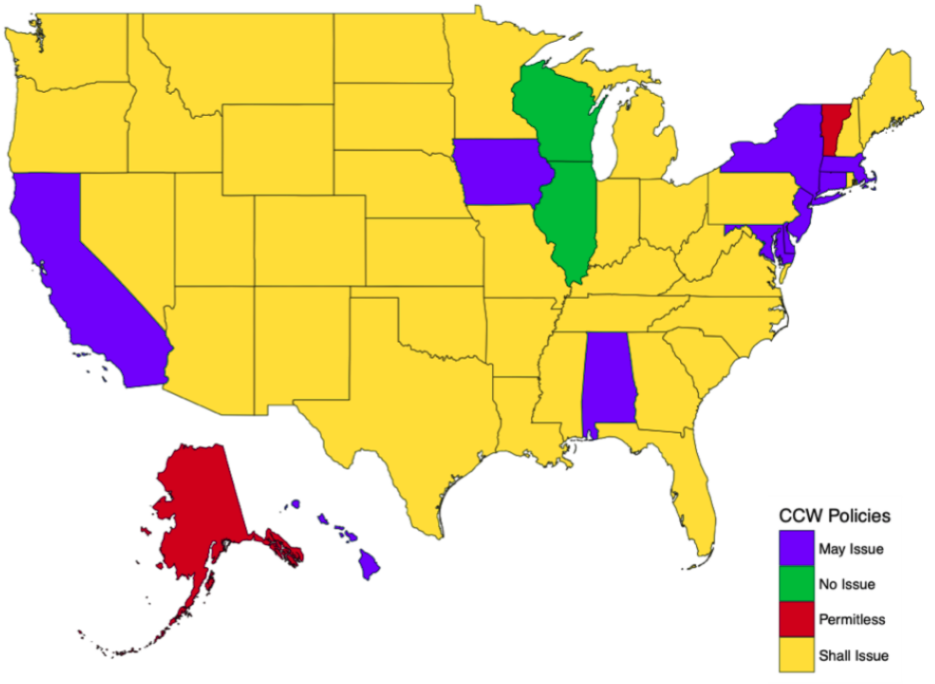

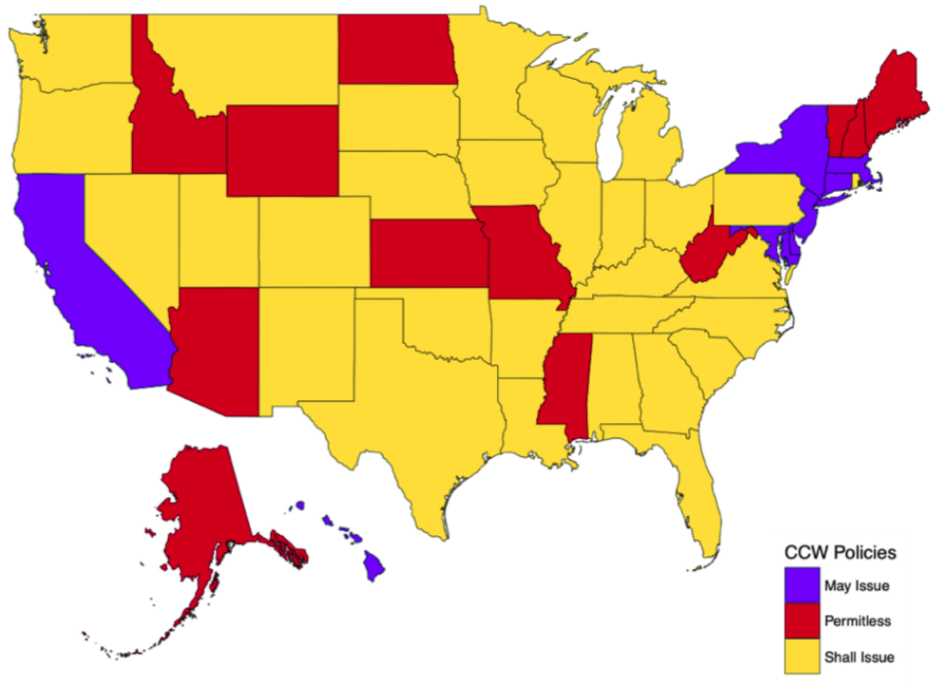

As of July 2019:

- eight states have may issue laws

- 29 states have shall issue laws

- 13 states have permitless laws

As seen above, most of the country falls into the shall issue law group, with 84% of states being “Right to Carry” states (42 of them).

Differences in Concealed Carry

Concealed carry laws vary significantly in their implementation and requirements, for example, in:

- what entity issues the permit (the state / the county / localities / courts)

- how long the permit lasts

- if college campus carry is allowed

- state residency requirements

- age requirements (18 / 21 / other)

- “good cause” requirements (dangerous job / safety threatened / etc)

- suitability requirements (health, criminal record, community reputation)

Generally, the amount of discretion that states have on whether they must issue a permit varies widely.

Training Requirements

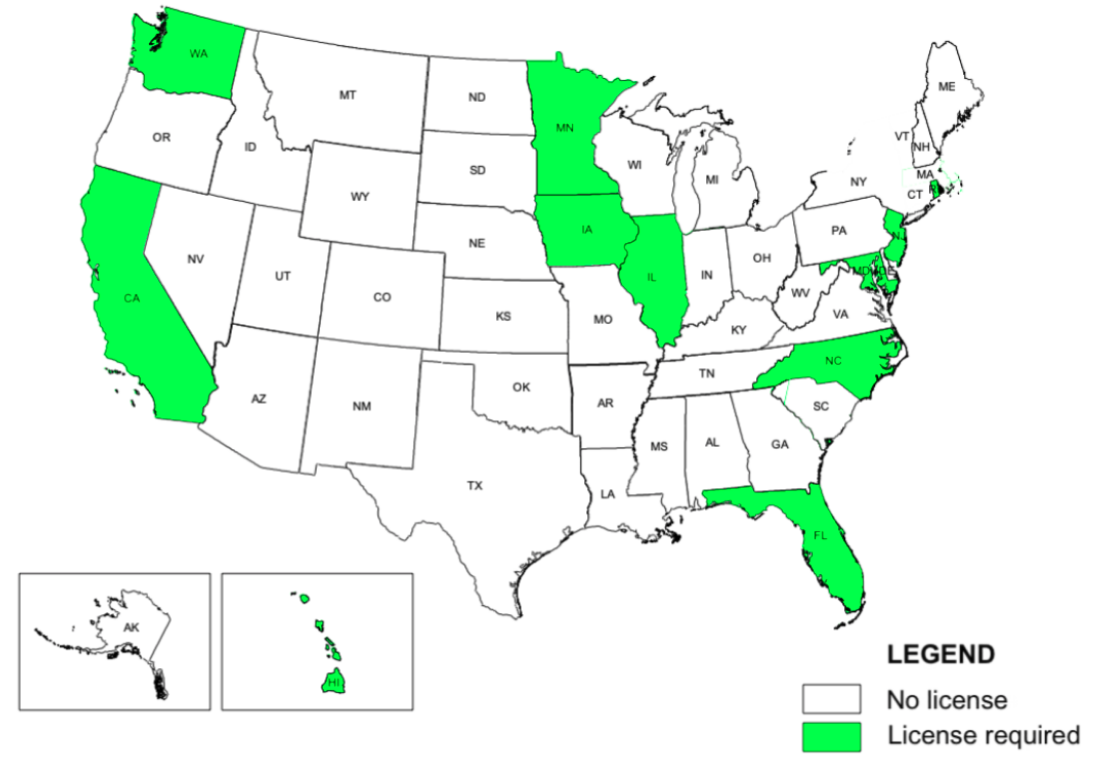

Training requirements for concealed carry permits vary significantly as well. Some states require specific courses that need be taken, such as safe storage, specific laws, or specific use cases for guns. Some states allow online courses.

A notable data point: of the 31 states that require training courses for concealed carry of a firearm, only 18 of them require actually firing a gun. In some cases, that just means “you’ve fired a gun on a firing range”, while others indicate some level of proficiency, such as target accuracy.

Yet, while it is good that 31 states have training requirements, none of those 31 require the applicant to demonstrate competency in decision-making with regards to firearms, such as knowing when it is lawful or justified to use a concealed firearm.

“Right to Carry” Laws

Over the last forty years, there has been a significant shift in the “Right to Carry” law landscape in the states.

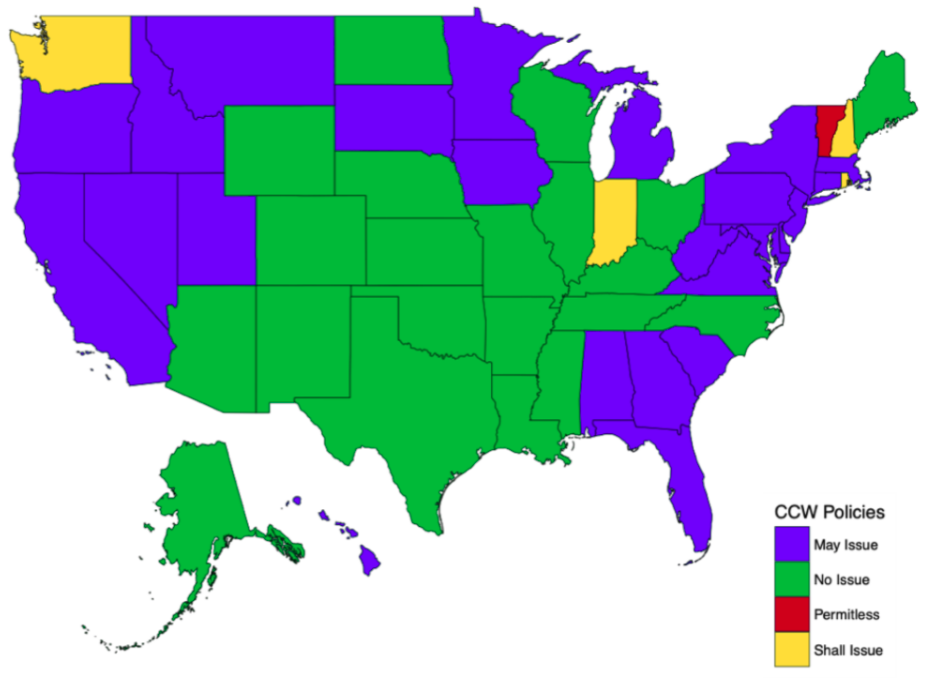

Concealed Carry Laws in 1980

In 1980, the majority of states were “no issue” law states – carrying a concealed firearm was not allowed at all. Many more states were “may issue” states (with strict restrictions), with three “shall issue” states. Only one state did not require any extra licensing or permit to carry a concealed firearm in most public spaces – Vermont.

Concealed Carry Laws in 1990

Fast forward ten years to 1990:

- More states became “shall issue” states, making it relatively easy for individuals who can legally own guns in their home to legally carry them in public and in a vehicle.

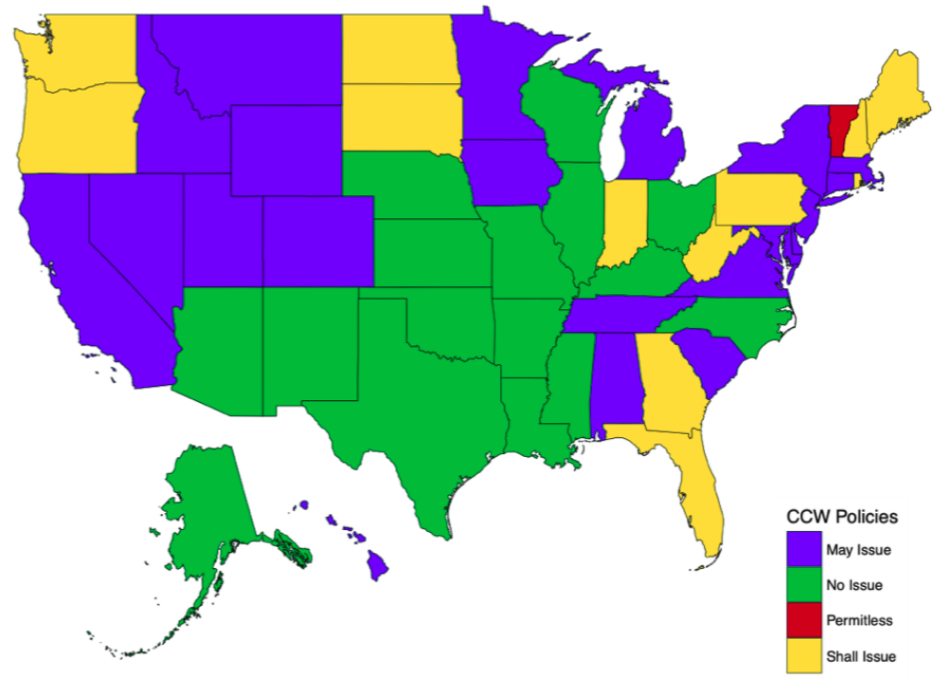

Concealed Carry Laws in 2000

Fast forward another ten years to 2000:

- More dramatic changes, with “shall issue” laws becoming the dominant laws across the states

- Few states with “may issue” laws

- Very few states with “no issue” laws

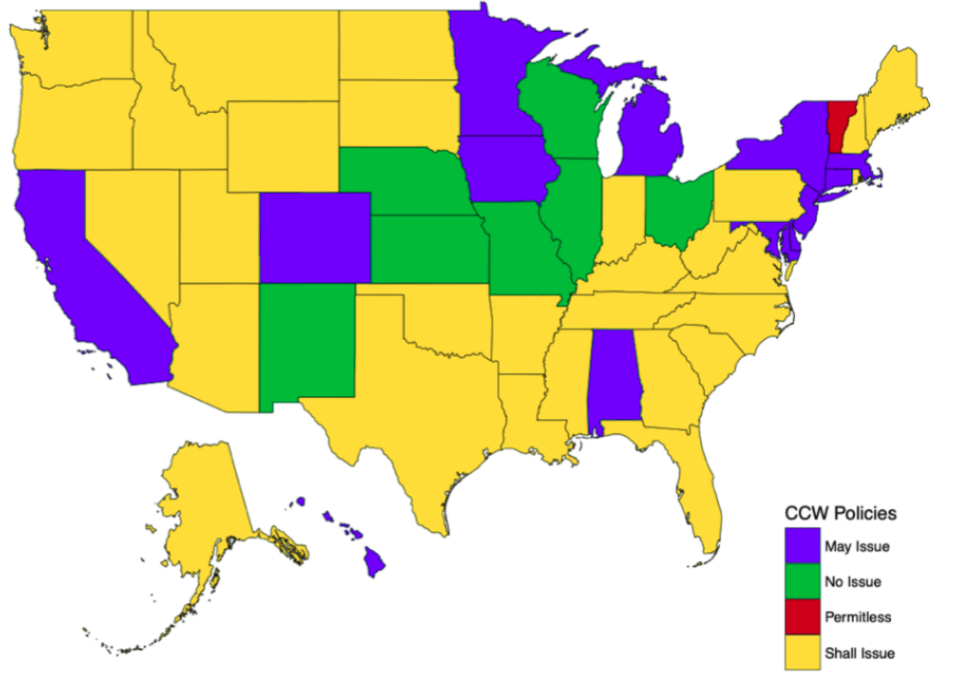

Concealed Carry Laws in 2010

Fast forward another ten years to 2010:

- Almost all states are “shall issue” states

- Alaska joins Vermont in being the second state requiring no permit or extra licensing to carry a concealed firearm in public spaces

Concealed Carry Laws in 2017

Fast forward seven years to 2017:

- Most states are “shall issue” states

- Twelve states require no permitting or extra licensing for carrying a concealed firearm in public

- Only eight states are restrictive “may issue” states

- No states prohibit concealed carry of firearms entirely

With all of this change, we can look at research on how this has affected society overall.

One of the first early research results showed, in 1998, that more people were carrying concealed guns as a result of these laws. The researchers theorized that this would deter and prevent crimes, and it presented evidence that this was the case. Unfortunately, the data and results were closely scrutinized and were found to have major data and research errors, invalidating the conclusions of this first study (sources: Crime and Deterrence, Firearms and Violence, Impact of Right to Carry)

Newer research, since that time, has uncovered a variety of effects about the rise of “right to carry” laws (source: Right to Carry Laws), primarily:

- Arming citizens in public does have benefits

- Some harm, violence, and crime is deterred

- Benefits are outweighed by the risks, however

- More harms, violence, and crime is actually created than is reduced

Why might this be the case? “Right to Carry” laws enable more guns to be available in public, both on a person and in vehicles for criminals to steal. Criminals might also suspect that in the course of committing crimes, they will have a higher chance of encountering an armed civilian, and so they themselves carry more guns during their criminal activities. Sometimes, these findings are directly connected to a rise in general fear in society that other people might be carrying guns, so individuals think the best thing to do is to carry a gun themselves. This leads to an “arms race” of civilians carrying guns in public.

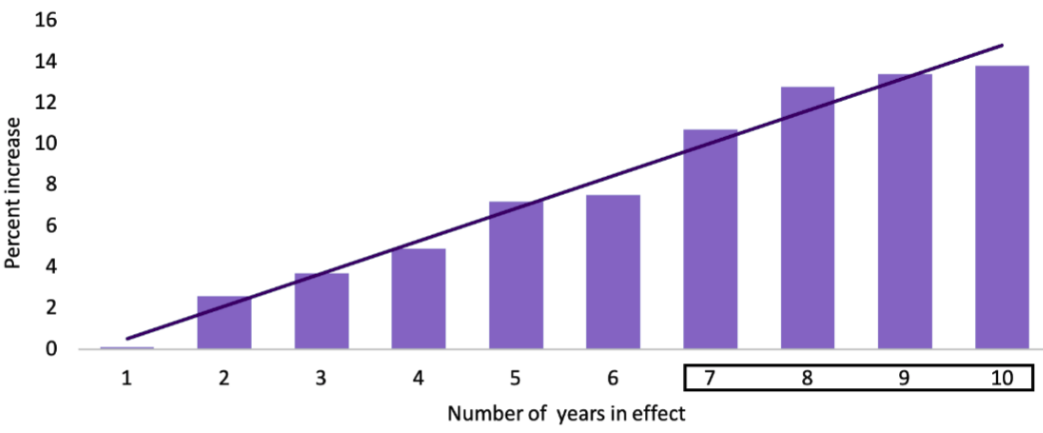

Percent increase in violent crime every year after a “Right to Carry” law is in effect (source: Right to Carry Laws)

A 2018 study looked at how “right to carry” laws are likely to have impacted violent crime rates over time, and found a clear link between the number of years that a “right to carry” law was in place and the percent increase in violent crime. After seven years, the increase in violent crime was statistically significant (essentially unmistakable), with an increase in 11 – 14% overall.

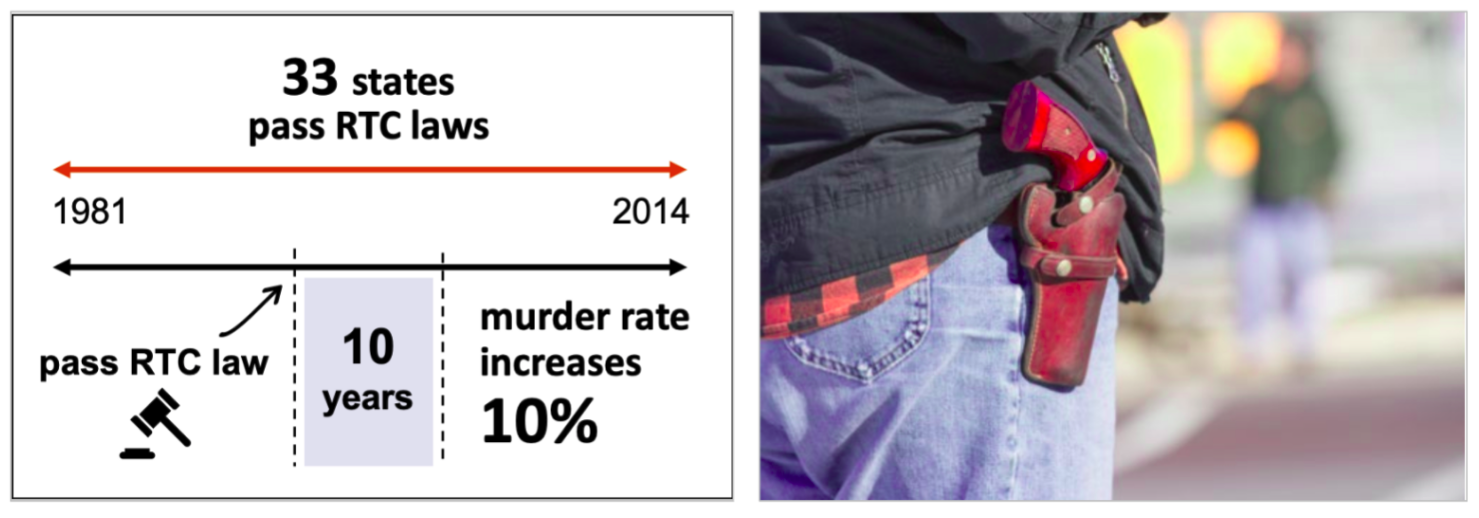

Also revealed in that study time period, in which 33 states passed “right to carry laws”,

- the murder rates were estimated to have increased by 10% during the ten year period after such laws went into effect

Two other studies in 2017 and 2018 looked at how “right to carry” laws impacted homicide rates, looking at states with “shall issue” laws. Those studies found (sources: Easiness of Legal Access, Homicide in Urban Counties):

- “right to carry” laws were associated with a 6.5% increase in overall homicide rates between 1991 and 2015

- “right to carry” laws were associated with a 7% increase in firearm homicide rates

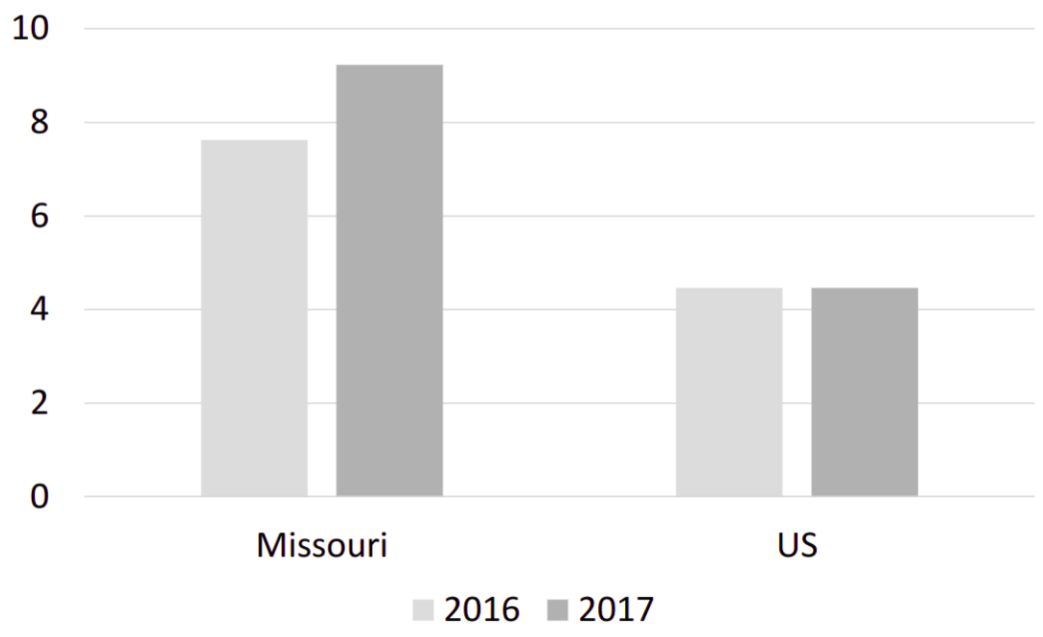

Change in Firearm Homicide in Missouri vs US, 2016-2017 (source: CDC WISQARS)

A final case study on “right to carry” laws: Missouri has greatly loosened restrictions on concealed carry of firearms over the last few decades. In 2017, it became a permitless concealed carry state. One year of firearm homicide data is available since it became a permitless state, and it clearly shows that rates increased from seven to nine homicides per 100,000 during that period, while rates stayed completely flat for the US overall.

“Stand your Ground” Laws

“Stand your Ground” laws define when it is legally justifiable to use lethal force, often referring to what is called the Castle Doctrine. While I’ll cover these laws in more detail later, in short, they say that when you’re faced with a dangerous situation, you are not legally obligated to retreat, and may use lethal force to defend yourself. The intent of these laws is to deter crime, under the hypothesis that if a potential burglar, robber, or assailant knows that a victim may defend themselves with lethal force, they may choose not to commit that crime.

“Stand your Ground” laws were first enacted by Utah in 1994, followed by Florida in 2005, and by 2018, 33 states had “Stand your Ground” laws. Some of the first studies of the effects of these laws include (sources: Evidence from Castle Doctrine, Homicide in Urban Counties, Unlawful Homicides in Florida):

- burglary, robbery, and violent assault rates did not go up or down by the passing of these laws. So hypothesis that crime would be deterred was disproven.

- homicides went up by 7 – 9% in large urban counties between 1994 and 2014

- very specifically, an increase in justifiable homicides in addition to non-justifable homicides

- homicides in Florida went by up an incredible 24% overall, including a 32% increase in firearm homicide, between 2005 and 2014

In short, the laws did not have the effect that they intended, and actually increased the rate of homicide.

The fact that concealed carry of firearms is now more accepted than it ever was before makes it important to keep these statistics in mind. As more people carry guns in public and have a legal justification for using their guns to defend themselves rather than trying to run away, it’s no surprise that the number of firearm homicides is up. In particular, in Florida, there were three times as many concealed carry permit holders in Florida in 2015 as there were in 2005 when the “Stand your Ground” law was first enacted (source: Evidence from Castle Doctrine).

One of the most famous highlights of “Stand your Ground” laws appeared in the slaying of Trayvon Martin, an unarmed 17-year old, in Florida. There is a substantial amount of research to show that there are implicit biases that are pervasive in the United States with regard to black individuals, especially black males. The implications of an ever-growing gun-carrying public may very well have serious implications on opportunities to act on racial bias in a lethal way.

Conclusions

Civilian Gun Carrying

- “Open Carry” is the visible carrying of a gun in public

- “Concealed Carry” is the non-visible carry of a gun in public. All states have allow concealed carry in some form.

- Three types of concealed carry laws exist at the state level:

- “May issue” (used by 8 states) – laws that have requirements and discretion over whether to allow an individual to carry a concealed firearm

- “Shall issue” (used by 29 states) – laws that have requirements but no discretion if those requirements are met

- “Permitless” (used by 13 states) – laws that do not require permits to carry a concealed firearm

- Requirements and discretion vary, including permit duration, residency and age requirements, suitability requirements, criminal record, etc

- Training requirements (31 states require this) also vary

- No training requirements require proof of understanding the legal uses of the firearm or proof of good judgment

“Right to Carry” laws

- “Right to Carry” laws embody that if requirements are met, the state must permit or allow concealed carry by a licensed individual

- Dramatic shift away from “No licensing” to “Shall issue” laws nationwide since 1980

- 1980: Five “Right to Carry” states (four “Shall issue” and one “Permitless”)

- 2017: 41 “Right to Carry” states (29 “Shall issue” and 13 “Permitless”

- “Right to Carry” laws have more negative effects that positive ones

- 11 – 14% increase in violent crime after seven years of having a “Right to Carry” law vs not having one

- 6 – 7% increase in homicide rates over a 25 year period

“Stand your Ground” laws

- “Stand your Ground” laws define when it is legally justifiable to use lethal force against rather than retreat from danger

- These laws do not decrease burglary, theft, or violent crime as they had intended

- They increase homicide rates by 7 – 9% in large urban areas over a 20 year period

- Over 20 years, Florida’s “Stand your Ground” law:

- increased the overall homicide rate by 24%

- increased the firearm homicide rate by 32%

References

- Crime and Deterrence – a flawed 1998 study claiming that concealed carry laws deter violence crime

- Firearms and Violence – a 2005 book which identified research and result errors in the Crime and Deterrence study above

- Impact of Right to Carry – a 2014 study continuing to examine and further refute the conclusions from the Crime and Deterrence study above

- Easiness of Legal Access – a 2017 study examining the relationship between “shall issue” laws, “may issue” laws, and homicide rates

- Homicide in Urban Counties – a 2018 study evaluating the effects of firearm laws on homicide in large, urban counties

- Right to Carry Laws – a 2018 study estimating the impact that adopting Right to Carry laws have on violent crime

- CDC WISQARS – a public database that provides fatal and nonfatal injury, violent death, and cost of injury data.

- Evidence from Castle Doctrine – a 2012 study examining whether aiding self-defense via standing one’s ground deters crime or, alternatively, increases homicide

- Homicide in Urban Counties – a 2018 study testing the effects of firearm laws on homicide in large, urban U.S. counties

- Unlawful Homicides in Florida – a 2017 study examing the association between the enactment of a “Stand your Ground” self-defense laws and Florida homicides

Which 2020 US Democratic Presidential Candidate’s policy views most align with mine?

Presidential candidates’ policy positions are just one reason to choose who to vote for in a primary election, yet it can often be difficult to determine what a candidate’s policy positions are, let alone with more than ten candidates.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

See the bottom of this post for photo credits.

In order to provide everyone with an easy way to determine which candidates are most like themselves, I created a candidate quiz and ranking tool. The quiz focuses on hot policy topics including health care, education, immigration, global warming, gun control, individual economics, foreign policy, and improving our democracy. You can answer as many questions as you want, and you can indicate how important each topic is to you personally. The more questions you answer, the more accurate your candidate ranking will be!

Clicking the link below will open a new quiz just for you in Google Sheets, which you will use to copy and fill out the quiz. It will be linked to your Google account, so you can bookmark it, close it and come back to it at any time. If you chose to close your quiz and continue later, use the bookmark of the quiz itself, rather than creating a new quiz (unless you’d like to start over!)

Frequently Asked Questions

Are you (or anyone else) viewing or collecting my quiz responses?

No. No one except you has access to your quiz responses, and there is no way that I or anyone else can view your quiz responses in the future, either. If you choose, you can share your quiz response with others, using Google Sheets sharing capabilities, which are turned off by default.

Do I have to answer every question?

No. You may answer as many questions as you like, and the questions that you do answer will be used to determine how closely matched you are to each candidate.

This quiz is really long! Can I come back to it later?

Yes! Once you start taking the quiz, you can bookmark the quiz page itself (not this page) and come back to it later. Note that if you click the link on this page again, you’ll start an entirely new quiz (though your old quiz responses will still be retained in your old quiz).

Photo Credits

Evidence-Based Policies to Prevent Gun Violence: Waiting Periods and Red Flag Laws

This is the tenth post in a series about Reducing Gun Violence in the United States. The previous post described Gun Dealer Oversight and Regulation.

In this post, I’ll explore using waiting periods and red flag laws to prevent gun violence.

For those who want to see the highlights without going through the data, skip right to the conclusions at the bottom of this post.

- The data in this post comes from several different sources, which I’ve linked in the references section at the bottom of this post for those who want to see the data for themselves or dive deeper.

Waiting Periods

Recall from my previous post on Background Checks that if a federal background check initiated at a licensed gun dealer is not completed within three days, the sale may proceed. Because of this relatively short period for federal law enforcement to complete a check, several states have “waiting period” laws to prevent a purchaser from obtaining their purchased firearm, and these range from three to fourteen days. During this waiting period, the purchaser may not take possession of their legally purchased firearm. These waiting periods have two primary effects:

- allow federal law enforcement more time to perform a background check

- add in a “cooling off” period to reduce the chance of a newly purchased gun to be used in an impulsive, harmful way

Many waiting period laws apply to all gun sales at licensed dealers, but a few only apply to handguns or certain types of long guns such as semi-automatic rifles.

States which require a waiting period before taking possession of a gun (source: Giffords Waiting Periods)

Ten states have waiting periods as of 2019.

Do waiting periods on firearm possession have any effect?

Waiting periods of taking gun possession are associated with (sources: State Firearm Laws, Looking Down the Barrel, Handgun Legislation)

- lower rates of guns moving from state to state for criminal use

- lower rates of firearm suicide (~ 3%)

Waiting periods have not been shown to have an effect on firearm homicide rates; unlike purchaser licensing requirements (which, by design, include built-in waiting periods).

Red Flag Laws

Red Flag laws are another method that has been shown to be very effective at reducing gun violence, in particular, suicide.

In many cases, the pretext for removal of firearms from a person is based on that person having a prohibited civil status, such as being a felon. These status categories, based on previous actions of the individual, do not cover many people who are not criminals, have no domestic violence history or history of institutionalization for mental illness. These individuals might show warning signs of violent behavior, such as (but not limited to) substance abuse issues, anger issues, or suicidal thoughts to which existing firearm removal laws do not apply.

Red flag laws, which exist at the state level, fill these gaps. In practice, red flag laws allow family members, intimate partners, or law enforcement to petition a court on their own for the temporary removal of a firearm from an individual who they think is at high risk of committing gun violence. These orders are known commonly as Extreme Risk Protection Orders (ERPOs), though states use different names for them. The individuals who can petition for removal vary depending on the state. A judge may issue what is known as an ex-parte order for the removal, meaning that the person deemed to be at risk does not need to be present before the order may be signed. If a court approves the order, the subject of the order has the opportunity to be part of a hearing of the court to challenge the order before it takes effect, where they are allowed legal counsel, and the state must provide clear and convincing evidence that the individual is still at high-risk. If either the subject of the order does not desire a hearing, or the court rules in favor of the state, the order directs law enforcement to temporarily remove all of the firearms from the subject. These orders are civil procedures, not criminal procedures, so they do not go onto a person’s criminal record.

States where red flag laws have been enacted and are being considered

Connecticut and Indiana were the first states to enact red flag laws, in the wake of publically notable shootings. Research on the use of these laws indicates that individuals subject to these orders typically have many guns – on average, seven per person. Because the majority of people who would use a gun to end their life would have been legally allowed to purchase one on the day of their death, the way most of these laws are used are by concerned family members who fear a relative is at high-risk for suicide.

Two studies have shown the effectiveness of these laws:

- A 2016 study has shown that for around every ten ERPOs issued, one life has been saved (source: Implementation and Effectiveness)

- A 2018 study showed that Indiana’s law decreased its firearm suicide rate by 7.5% and Connecticut’s law decreased its firearm suicide rate by 13.7% (source: Effects of Seizure Laws)

Red flag laws have been implemented in 17 states as of 2019 and, depending on the state, have different names for the orders that they allow:

- Extreme Risk Protection Orders

- Risk-based gun removal orders

- Red-flag law orders

- Risk protection orders

- Gun violence restraining orders (GVROs)

- Proceedings for the Seizure and Retention of a Firearm

- risk warrants

Conclusions

Waiting Periods

- State waiting periods laws address weaknesses in federal firearms laws

- Only ten states implement waiting periods as of 2019

- They give law enforcement more time to perform background checks and create a “cooling off” period for buyers who might use firearms impulsively

- Waiting periods:

- decrease rates of guns moving from state to state for criminal use

- decrease rates of firearm suicide

Red Flag laws

- State red flag allows allow proactive, temporary removal of firearms from individuals deemed to be at high-risk for firearm violence

- Orders are commonly known as Extreme Risk Protection Orders

- Family members, intimate partners, and law enforcement are commonly enabled to petition a court for proactive removal

- Individuals subject to an order may have legal counsel and force the state to show clear and convincing evidence before an order goes into effect

- Studies in Indiana and Connecticut show a 7.5% and 13.7% reduction in suicide rates, respectively

Next up: Civilian Gun Carrying

References

- Giffords Waiting Periods – a website showing use of waiting periods in different states

- State Firearm Laws – a 2018 study examining the relationship between state firearm laws and the extent of interstate transfer of guns

- Looking Down the Barrel – a 2017 study examining the effect of purchase delays on firearm-related homicides and suicides

- Handgun Legislation – a 2017 study examing the extent to which four laws regulating handgun ownership were associated with statewide suicide rate changes

- Implementation and Effectiveness – a 2016 study examining the effects of gun removals in Connecticut following its ERPO law

- Effects of Seizure Laws – a 2018 study evaluating whether risk-based firearm seizure laws in Connecticut and Indiana affect suicide rates