This is the fourth post in a series about Reducing Gun Violence in the United States. The previous post described Firearms and Suicide.

In this post, I’ll explore federal, state, and local powers to regulate guns, the second amendment to the U.S. Constitution, litigation as a public health strategy, and obstacles to research, gun policy, and transparency.

- For those who want to see the highlights without going through the data, skip right to the conclusions at the bottom of this post.

Federal, State, and Local Powers to Regulate Guns

Governments can pass laws and create regulations to prevent gun violence. In the United States, these laws and regulations are created at the federal, state, and local level. As a civics refresher, there are three branches of government, each which play a different role in reducing gun violence:

- the legislative, or law-making branch

- the executive, or law-enforcing branch

- the judicial, or law-interpreting branch

The Federal Government

Congress (the legislative branch of the federal government) only has powers that are granted to it by the Constitution. The Second Amendment to the Constitution, for example, limits the powers that Congress has with respect to guns – more on the Second Amendment below. Congress has passed three major pieces of gun-related legislation:

- The Gun Control Act of 1968 (GCA)

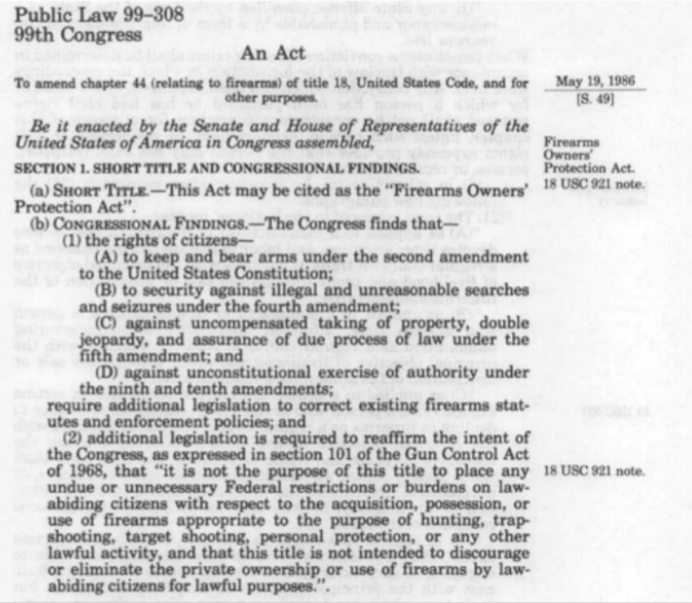

- The Firearm Owners Protection Act of 1986 (FOPA)

- The Brady Handgun Violence Protection Act of 1993 (Brady Act)

The Gun Control Act of 1968 described the basic method for regulating gun sales and firearm dealer licensing and added some new prohibitions for importing certain guns – only for use for sporting purposes. It also created some categories of people to whom guns could not be sold:

- felons

- unlawful users of illegal substances (drugs, for example)

- people committed to mental institutions

The Firearm Owners Protection Act of 1986 reduced restrictions on selling guns without a license, which made private sales easier. It made it harder to convict dealers who sold guns illegally (and reduced penalties for doing so), and limited federal compliance inspections for licensed dealers. It banned computerized records of these inspections and banned federal government collection of firearms purchased and sold.

The Brady Handgun Violence Protection Act of 1993 created the background check requirement for licensed gun dealers and instituted the National Instant Criminal Background Check System, which went into effect five years later in 1998. It’s important to note that background checks were not created for private sales, but only if you purchased a gun from a retailer, like Walmart or Dick’s Sporting Goods.

Generally speaking, federal laws act as a minimum of gun restrictions, preventing some people from purchasing guns but not all. Here are some things federal laws do not do:

- require background checks or record keeping for private sales

- for example, selling a gun to someone you meet on Craigslist

- regulate or prevent gun carrying in public

Federal Regulations

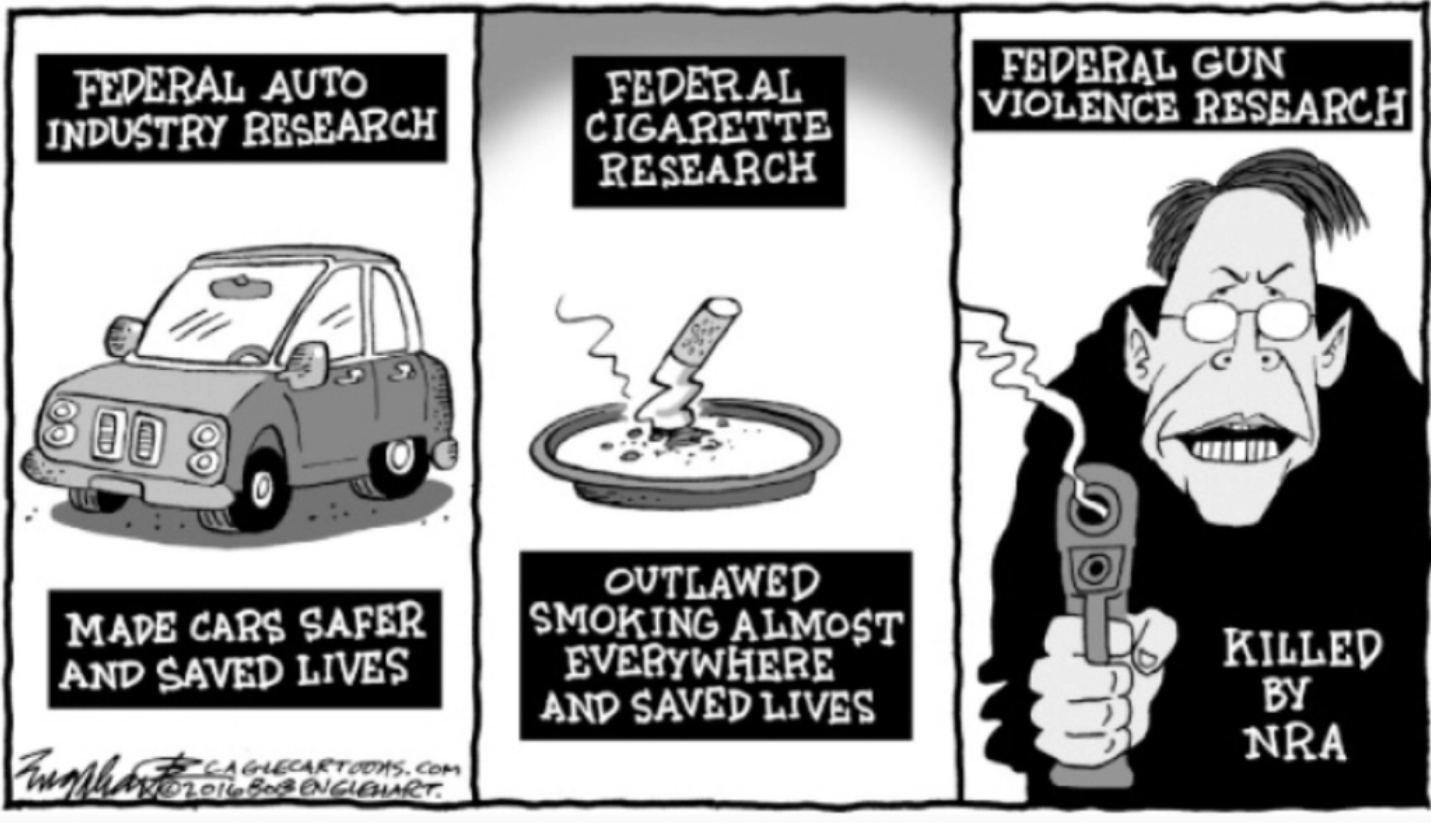

In addition to laws passed by the legislature, the executive branch (the “administration” headed by the President) may create agencies that create federal regulations. Federal agencies create rules and enforce laws passed by Congress. For example, the Federal Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms regulates guns, but it is severely limited in its ability to do so by Congress’s laws. In fact, no federal agency has complete control over gun regulation, which makes it challenging to create meaningful restrictions at the federal level. This is in contrast to other products, such as cars, that the federal government regulates extensively through safety standards such as airbags, seat belts, highway safety, and so on.

State Governments

By way of the Tenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, those powers not granted explicitly to the federal government are reserved for the states. For example, one of the powers left to the states is police power – the ability for states to create police forces to protect the public. The police power is particularly important for preventing gun violence.

States can and do more with respect to gun laws than the federal government does; they may include extra restrictions or standards for ownership. In fact, most gun laws exist at the state level. Those laws might:

- require training before purchasing a gun

- prohibit those with violent misdemeanors from owning a gun (not just felons)

- create a system for private sale background checks

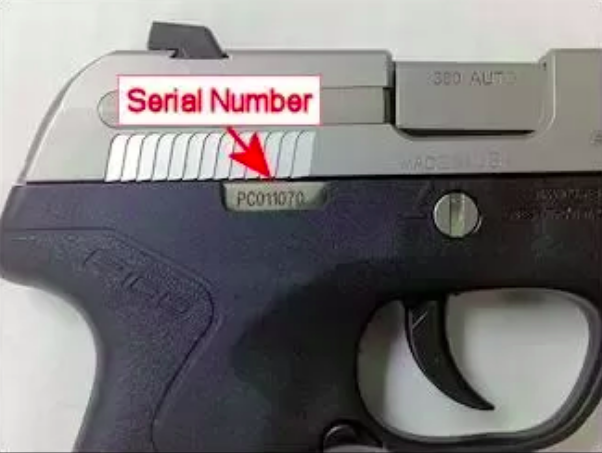

- register handguns or collect serial numbers

- restrict who can carry a weapon in public

- regulate the sale and ownership of assault weapons or smart guns (which can only be fired by authorized users)

Local Governments

Local (aka city, or municipal) governments have the least amount of power to regulate gun violence, but they feel the brunt of that violence themselves. They have police power, like state governments, but that power is granted by the state governments themselves and is often limited by something called preemption.

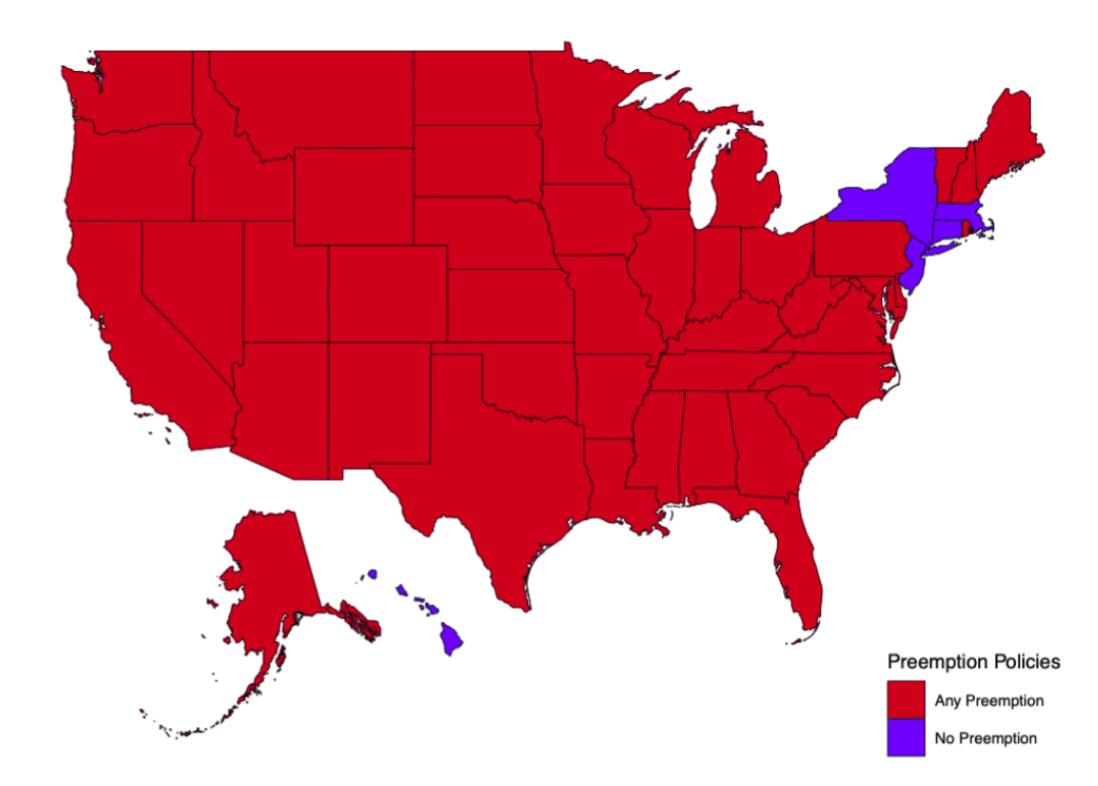

Preemption allows a state government to forbid local governments from passing certain laws. Most local governments are granted powers to protect their citizens, but local firearm regulations are often disallowed. For example, a state may prevent a city from passing their own gun regulations.

Only five states allow their local city governments to pass more strict firearms laws than state law. These states are:

- Hawaii

- New York

- Massachusetts

- Connecticut

- New Jersey

The Second Amendment

The Second Amendment to the U.S. Consitution states that the right of the people to keep and bear arms shall not be infringed.

Sounds pretty clear, right?

It turns out that the full text of the Second Amendment is actually: “A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.”

What does that mean? That somewhat convoluted text was written in the 18th century, and so it’s sometimes hard to figure out what the framers meant by this. So who gets to decide?

- Advocacy groups, like the NRA or the Coalition to Stop Gun Violence? No.

- The public? No.

- The media? No.

The legal (and practical) reality is that the courts, or the judicial branch of the government, decides what this language means. It’s a very important fact, so it bears repeating:

The Second Amendment means what the courts say it means; not Congress, not the American public, not the media, and not advocacy groups.

Until recently, no federal court has ever struck down a gun law as violating the Second Amendment. For example, a law that the Supreme Court has not struck down as in conflict with the Second Amendment:

- A 1939 law that regulates sawed-off shotguns and machine guns

- Does not protect guns that do not have a “reasonable relationship to the preservation or efficiency of a well regulated militia.”

In 2008, a landmark court ruling by the Supreme Court in District of Columbia v. Heller did overturn Washington, D.C.’s almost complete ban on the right for people to own handguns in their own home. The court, in its ruling, voted 5-4 to strike down the law, saying that individuals have the right to have a handgun in their home for protection. However, it did not comment on whether individuals have the right to carry guns outside of their home, or how many guns they are allowed to own, or anything else. In fact, the Supreme Court went as far as to say:

“… nothing in our opinion should be taken to cast doubt on longstanding prohibitions on the possession of firearms by felons and the mentally ill, or laws forbidding the carrying of firearms in sensitive places such as schools and government buildings, or laws imposing conditions and qualifications on the commercial sale of arms.”

Lower federal courts and other state courts have upheld almost every other gun law – thousands of other laws – other than bans on private handgun ownership. Those laws which have been upheld as fully constitutional include restrictions on:

- open-carry of guns

- concealed-carry of guns

- military-style weapons

- high-capacity magazines

- felons from owning guns

Still, the Supreme court has left many questions open on gun ownership. The big takeaway is that it has not interpreted the Second Amendment to prevent governments (federal, state, or local) from creating reasonable restrictions that promote public safety and help to keep guns out of the hands of people who are likely to harm others.

Litigation for Public Health

Litigation, or using lawsuits, is another way to protect public health. It can help to improve public health by financially incentivizing gun manufacturers and retailers to change the way that they create and market guns. Sometimes, litigation can even raise public awareness of the way that guns are made or marketed which can lead to new laws.

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, there were many lawsuits filed that targetted firearm manufacturers and dealers, some that were initiated by states and some by cities. Those lawsuits argued that gun manufacturers and dealers marketed their guns in a way that caused injuries (including death) and created other costs, and those lawsuits sought monetary damages. The costs, direct or indirect, included things like loss of economic value of life, lower property values, and emergency department fees.

If that sounds familiar, those lawsuits follow the same pattern of those that were filed against the tobacco industry years before and were largely successful.

There was a major reaction to these flood of gun lawsuits which was the creation of the Protection of Lawful Commerce in Arms Act of 2005. It severely undermined using litigation as a public health tool, as it provides broad protections to gun manufacturers and dealers from legal liability which almost no other consumer product in the U.S. market has. In addition to that protection, people harmed by gun violence have no legal remedy when they are affected – no pool of money is available to help victims of gun crimes, unlike, for example, persons injured by vaccines.

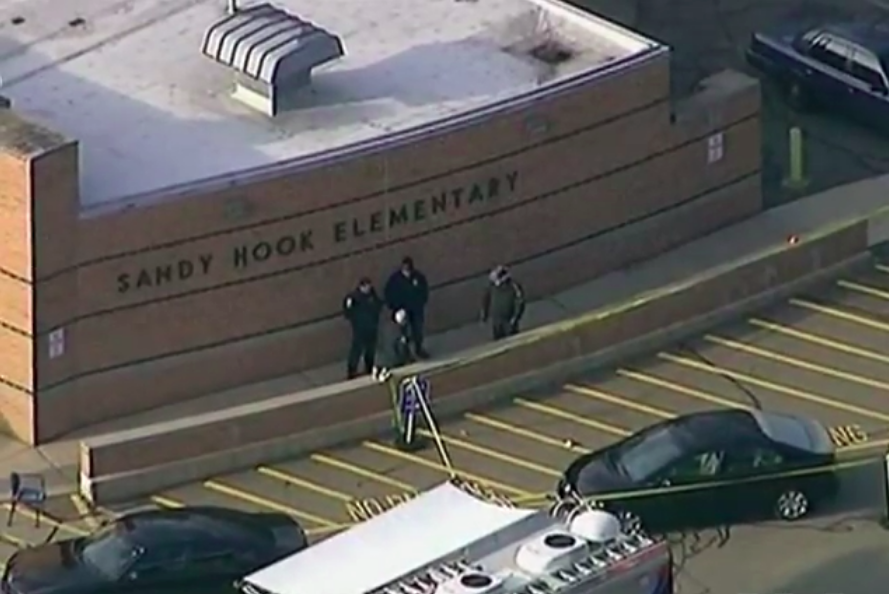

There have been some notable exceptions to the PLCAA’s power. For example, a lawsuit filed in the wake of the Sandy Hook shooting, Soto v. Bushmaster, alleged that the manufacturer of one of the weapons used in the shooting, Bushmaster, presented its marketing in an “unfair, unethical, or dangerous manner” and sought to “expand the market for [its] assault weapons through advertising campaigns that encouraged consumers … to launch offensive assaults against their perceived enemies”. The lawsuit was determined by the Connecticut Supreme Court in March 2019 to not be protected by the PLCAA, and is being allowed to move forward.

Obstacles to Research, Policy, and Transparency

Two particular laws have caused issues with research and policy development with regards to firearms. These are:

- The Dickey Amendment of 1996

- The Tiahrt Amendment of 2003

The Dickey Amendment

The Dickey Amendment is a provision first inserted into a 1996 federal spending bill, which mandated that:

- “none of the funds made available for injury prevention and control at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) may be used to advocate or promote gun control.”

While the Dickey Amendment only prevents money from being used for advocating or promoting gun control, it has also had a chilling effect on gun research at the CDC in general.

The Tiahrt Amendment

The Tiahrt Amendment is a provision of a 2003 federal money appropriations bill that

- limits the availability and use of gun trace data, by prohibiting the ATF from releasing that data to anyone other than a law enforcement agency or prosecutor in connection with a criminal investigation.

- prohibits the ATF from requiring gun dealers from doing inventories of their firearms as part of compliance inspections

- requires the FBI to destroy firearm license background check data within 24 hours after a background check is complete

In 2012, a study of a specific gun dealer showed that the institution of the Tiahrt Amendment was associated with an increased level of guns flowing illegally from dealers to criminals, and at a higher rate.

Overall, these laws make it harder for researchers and policymakers to access data and make factual conclusions and recommendations about preventing gun violence. Even when individual state lawmakers have good policy ideas, law enforcement is restricted in its ability to implement those policies and trace guns used in crimes.

Conclusions

- Gun laws are written at federal, state and local level, though federal laws are mostly bare minimums and state laws make up the bulk of gun laws

- Most states prohibit cities from passing gun laws that are more strict than state law

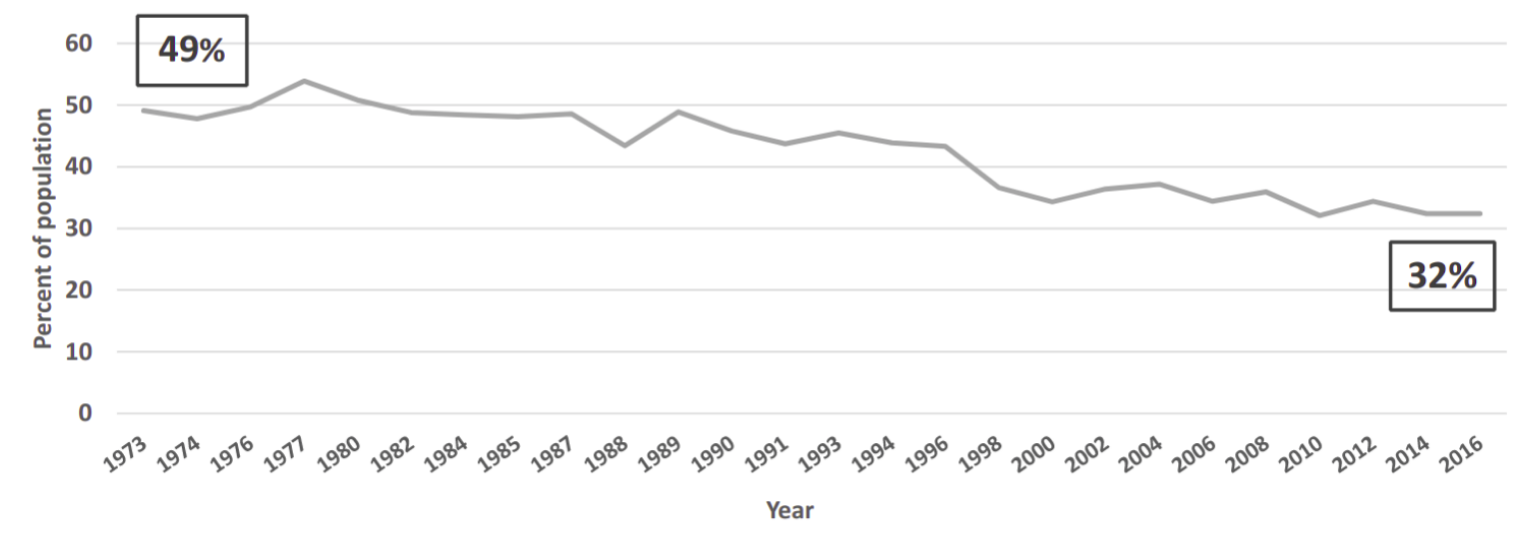

- The Second Amendment to the U.S. Constitution (the “right to bear arms”) means what the courts say it means

- And this is disconnected from what many Americans believe that the Second Amendment means

- Almost all gun laws have been deemed lawful and constitutional as long as they do not prevent a law-abiding person from owning a handgun in their own home for their own protection

- All gun laws prohibit felons from having or owning guns

- Additionally, individual states impose a variety of other constitutionally valid restrictions on gun ownership

- Legislation is a powerful tool to prevent gun violence, but it also puts restrictions on how gun ownership, licensing, and crime trace data is used

- The Dickey Amendment prevents the CDC from using federal money to advocate or promote gun control

- The Tiahrt Amendment severely limits the availability of gun trace data, shields gun dealers from doing inventories of their guns, and forces rapid destruction of background check records at the FBI

- These laws make it hard for researchers to determine what works best to prevent gun violence and prevents policymakers from implementing sound recommendations

Next up: Age-Related Firearm Restrictions and Safe Storage Laws